Nevertheless there are some major errors in logic, and a repetition of a troublesome theme of his, which I think merit a line by line criticism.

|

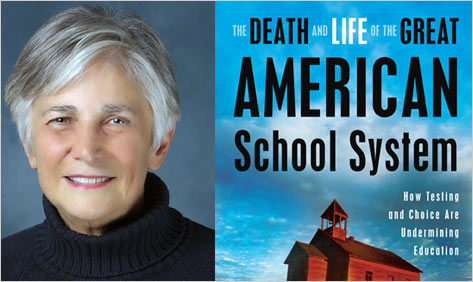

| Diane Ravitch with a book she recently poured out |

But you know who else is prolific? Appearing on TV and in the NYT? Writing books? Giving readings? David Brooks. I don’t see anyone debunking Brooks based on the quantity of his output. What hypocrisy for people as prolific as Brooks to resent the attention that Ravitch gets. They should acknowledge two things. First, she cultivates attention by listening to the educators. She is also is an amazingly effective social networker, publicizing teachers' own words along with her own frequent pithy, twitterific turn of phrase. Brooks, being a good writer himself should realize some of Ravitch’s popularity is due to rhetorical skill as well as to audience cultivation. Second, Ravitch touches a nerve. Her power comes not from her awesome institutional power as a Professor at NYU, or from her bully pulpit as a columnist at the New York Times (oops, sorry, that's Brooks), but from the fact that she expresses what so many people are already thinking and feeling, and she is rare in the national media for doing so.

The next paragraph is a straw man (see Paul Thomas' response), but a critical one in the education debate as it highlights what many reformers misunderstand about Ravitch, and misunderstand about resistance to current top-down reform efforts. Brooks identifies these as “the party-line view of the most change-averse elements of the teachers’ unions:”

There is no education crisis:

This is an oversimplification. The argument that Ravitch and many others (if Brooks bothered to read one of her books, he might realize this) isn’t that there is no education crisis, but that this claim rests on two false assumptions. First, there is no single American educational system. Well-off suburban schools have been turning out well-educated future professionals for quite some time now. Second, the current crisis rhetoric ignores the historical data. Ravitch is a historian, and has seen the permanent educational crisis described in every decade of the 20th century. She claims that our present moment is not unique.

Poverty is the real issue, not bad schools.

Again, an oversimplification, but one that Ravitch comes a lot closer to making. But saying “real issue” here obscures Ravitch’s point. While Ravitch may say that addressing poverty with a holistic program (like, hmm, Harlem Children’s Zone, maybe?) is better educational policy than test-based accountability, she is not a nihilist who thinks “bad” schools don’t matter. She is simply saying that poverty is a greater predictor of academic achievement (yes, even test scores) than reformers want to acknowledge, and that trying to identify and punish bad schools is not an effective way to improve them.

We don’t need fundamental reform; we mainly need to give teachers more money and job security.

What does “fundamental” mean here? Ravitch knows that reformers of every age have pledged that the school system needs to be “fundamentally” reformed. Many teachers know this firsthand, suffering from “reform fatigue” as every new turnaround expert boasts of fundamental change. When ed reformers of all stripes use the word “fundamental reform” it means “the way I want to redesign the educational system.” Everyone involved in this debate wants reform. There are many dimensions of reform possible. From class size, to school size, to curriculum, to who is teaching, to how we train them. Take Diane Ravitch, Leonie Haimson, Deborah Meier, E.D. Hirsch or any number of other people involved in education reform for a long time, and you will find many different ideas for reform. Please stop calling your own approach “fundamental” and everyone else’s ideas “change averse” without bothering to understand them. Most of these people have been trying to change the system for most of their careers.

At this point, Brooks steps back from the straw man (Look how reasonable I am! I am not going to attack this straw man I have shoddily erected, I’ll just be passive aggressive and undermine my opponent before I show how reasonable I am and admit that despite her overall craziness, she has some good points). Brooks acknowledges that teaching is a “humane art built upon loving relationships between teachers and students.” A system designed to improve multiple choices test scores distorts that.

At this point, I must acknowledge that that I continue to read Brooks for a reason. His willingness to acknowledge points of the other side does bolster his credibility. “If you make the tests all important, you give schools an incentive to drop the subjects that don’t show up on the exams but that help students become fully rounded individuals. You may end up with schools that emphasize test-taking, not genuine learning” Acknowledging the tension between testing and the humane nature of education buys him back into my good graces.

Oh, wait. I missed that word. “may” As it turns out, this incentive doesn’t have to work the way Brooks says it “may.” Why not? The dehumanizing testing incentive can be overwhelmed by the magic of

Some evidence? No cherry picking here! Oh wait, just kidding. Carolyn Hoxby’s results of studying charters in New York and Chicago. New Orleans (yes, where Arne Duncan said that Katrina was the best thing that happened to the education system there) has doubled the percentage of students performing at basic competency levels and above (yes doubled! Right here in River City! That’s double with a capital “D” that rhymes with “C” that stands for charter school!). What, you are skeptical of doubling academic achievement in a couple of years. Are you a status-quo defender?

|

| Taste our invigorating moral culture, vile illiteracy! |

The kind of presentation of evidence Brooks engages in here is reminiscent of Matt Yglesias with the magic of bourgeois modes of behavior. They dispense with the first criticism of selection bias (using a lottery study, or a single case study but ignoring other sources of selection bias) and trumpet the new uniforms. This reminds me of many shoddy popular interpretations of psychology experiments. Just because you have dealt with one third variable problem (selection bias) does not mean you get to say that now correlation really does mean causation.

But I don’t hate charter schools. And neither does Ravitch. I would love to see some of the elements of KIPP and Harlem Children’s Zone see more wide acceptance. For one: addressing poverty takes time and money. Rather than trumpet miracle schools that have amazing results with the power of mission, or leaders, or spiritual fervor, acknowledge that money helps when spent wisely, on things that Ravitch wants it spent on, like chess, Shakespeare, philosophy, or the arts, or foreign languages.

Brooks saves his most dishonest, victim-blaming paragraph for near the end, and almost makes me re-read Myers’ epic rant to fortify myself:

The places where the corrosive testing incentives have had their worst effect are not in the schools associated with the reformers. They are in the schools the reformers haven’t touched. These are the mediocre schools without strong leaders and without vibrant missions. In those places, of course, the teaching-to-the-test ethos prevails. There is no other.The reformers have touched every single public school in our country. NCLB and RTTT have ensured that is the case. By elevating testing in reading and math as THE incentive that matters, accountability-based reformers have demanded change from every single principal, and every single superintendent in the country. But where does this testing have the most impact? In the “failing” urban schools (although don’t worry, we’ll all be failing soon). The highest demands, the most intense pressure is felt by those places that had the most children in special ed, the most children in poverty, the most crumbling school buildings, the least amount of cultural capital, the least potential for PTA fundraising, the least number of functioning bathrooms, the least experienced teachers. But no, that doesn’t matter to Brooks. All they need are strong leaders with vibrant missions. No matter how many times Brooks goes to his thesaurus for “alive” (“alive” “vibrant” what’s one more… oh, how about “invigorating” “passion”) it doesn't hide his privilege, callousness and ignorance.

I went to DC Public Schools, I worked with a few principals after college in a brief volunteer stint for Hands On DC. My dad has taught at my high school for 15 years, my wife taught at another one for 8 years. The problem is not mediocre people. Please stop handing a charter principal a multi-million dollar budget and a development office and turn around and tell the public school principals to stop being mediocre and work harder on being outstanding with a sense of mission. When charters have as little resources as public schools, they struggle.

At the end of the column, we finally get the Brooks final solution, so much more reasonable than Ravitch: “The real answer is to keep the tests and the accountability but make sure every school has a clear sense of mission, an outstanding principal and an invigorating moral culture that hits you when you walk in the door” You know what, I love my kids' public school. I can volunteer there (to teach chess!) because I am a professional with flexibility in my hours. There is a great principal and a wonderful staff of hard-working teachers. But what makes this school work so well? Dedicated professionals. Active PTA and parent community. A state and district that funds reading aides and math aides (scroll to the bottom), and lower class sizes. An office staff and a full time nurse.

I’ll fight to protect my school with dedicated professionals with resources, a caring community with time and money to give, and a curriculum as full of "interesting science facts" as my son says. And I'll advocate to give the same to as many kids across the country as we can.You can keep your invigorating moral culture, David Brooks.

7 comments:

My 13-year-old daughter does well in school and well on tests. This summer she is taking humanities and science 5 hours a day, for 5 weeks. Many evenings, my husband or I, both professionals with graduate degrees, spend hours helping her understand plate tectonics, the Renaissance. She signed up for the program on her own but we were so pleased that she did that we promised her an iPhone 5 at the end of it. Because it's 10 miles away, one of us gets up at 6:30 every morning to get her dressed and to school by 8. One of us takes off work for an hour to pick her up at 12:45. The program is free and offered through the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. Is it the moral culture that explains her performance? Is it the hard work of her teachers? Is it the beautiful campus? Or is it all of the resources poured into her? I'd say it is some of all of those but the latter explains a huge amount of variance.

Another view of Brooks: http://conorpwilliams.wordpress.com/2011/07/01/david-brooks-educational-theorist/

@AnnMaria Thanks for sharing that story, that sounds like a great program. Free too!

The question to me is exactly as you pose it, what is the percent of variance explained?

It reminds me of the case where someone is proposing some new miracle medicine that cures what ails you, but no one knows why. Let's say we do a double blind clinical trial, and find out that it really works. Great. But before we start selling it nationally, let's figure out which of the ingredients are most important. Which ones are effective? Most snake oils made you feel better because they had a bunch of grain alcohol.

@Anonymous : Thanks for that. I appreciate reading this, and I don't dispute that the writer's (yours?) charter school worked very well. Let's support that charter school, by all means. But when the author claims that

"When it comes to urban education, the most reform-oriented schools are out-performing their counterparts by FAR (for an instance of how education reform opponents have gone wrong, see Linda Darling-Hammond’s recent catastrophe here), and by almost all measures"

I am skeptical. I don't accept that "reform-oriented" is a useful category here. Which reforms? Do you mean KIPP? Do you mean charter? Do you mean test-based accountability? Do you mean merit pay? From the studies I have seen (Fryer's, Hoxby, Credo) the results are much more mixed.

I think one thing the Brooks column highlights is the uselessness of broad categories of "pro" and "anti" reform. There are many dimensions of reform and we shouldn't treat KIPP or HCZ, or charters as one unified "treatment."

Great writing n great passion... To me it's very simple. Charters cause segregation by test scores and since test scores positively correlate with poverty and ethnicity, it is illegal to use public funds for these schools.

It's the testing we need to do away with but if we must we shoul use portfolio assessment where we teachers bubble up assessments n feed it into the data mining data bases if we must.

http://specialedvice.blogspot.com/

@ Anonymous 2: I agree on the benefits of portfolio assessment. I am not sure that all charters necessarily segregate based on poverty, but I think the incentives are too hard to resist to nudge out low scorers (public schools do this too, but don't have the same tools at their disposal).

I think charters can fill a role (more like Albert Shanker originally intended) but that role is not replacing traditional public schools, but complementing them.

There is due process in public schools and very little public oversight let alone due process in Charter schools across the country.That is the root of the problem. You can't forgo public oversight for the sake of some possible future miracle innovation, and you certainly can't gamble on the good intention of some obscure board of directors following the letter and intent of the fourteenth amendment.

The evidence of charter school segregation are mounting and the NAACP got it right to file a lawsuit. I am making an effort on my side of the country to stop this madness too and I appreciated your sharp, informed and good nature writing so much that i would like to maintain contact with you. My email is momzer@verizon.net.

We can experiment with school innovation while keeping public oversight and we should. My cousin who I am trying to convince to write a book about the power and influence of the mega foundations said while texting a few days ago: a little sun light is the best disinfectant. I fear this charter school thing and the testing is fast mutating out of the reach of antibiotics.

I agree that there are diverse education systems across America.

Post a Comment