Here is the quote:

Disciplines like functional neuroimaging (which shows us how different thoughts and actions activate different brain regions) have only been around for a couple of decades or less

|

| Look at my beautiful brain! |

I think we can understand a lot about the nature of science by studying the history of science, and distinguishing questions from tools, so here is my contribution to correcting that misconception.

The field of cognitive neuroscience is actually quite old. What is the connection between our biology and our thoughts? How does our brain create our mind? This question has been around longer than any consensus that our brain does create our mind, to the very beginning of biology itself. And scientific reasoning (however basic) has been used from the start.

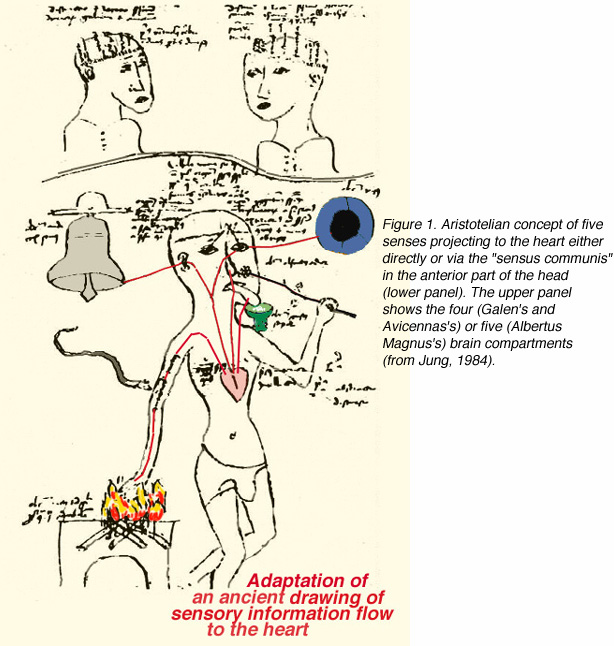

We start with Aristotle, who thought that the brain was responsible for cooling the blood, while the heart was the seat of reason. Why? One can survive a blow to the head, but not to the heart. The heart must be more important for conscious thought.

Of course, he was wrong, but his logic was impeccable, and forms one third of the logic of modern cognitive neuroscience.

There are three basic ways that cognitive neuroscience gains knowledge about the brain. This is not the only way of classifying the logic of cognitive neuroscience, but it nicely draws attention to the history of evidence in cognitive neuroscience.

1) We observe a change in behavior, due to known injury or biological disease . We classify this behavior. Then, we figure out where, and how, their brain injury (or disease) correlates to their behavior. In this case, the behavior is known first (think, memory problems in Alzheimers, or amnesia after an accident) then later the biological basis is described. I will discuss this part today, and continue with the others tomorrow.

2) A known part of the brain is either injured or stimulated (on purpose). In this case, we know the part of the brain injured (technical term: lesioned) and then we observe the corresponding behavior change.

3) A normal subject is asked to do a task. While they are doing the task, a scientist observes their brain.

We combine these techniques, inherently "connnective" with basic psychology (a pure psychological task, with psychological measure) and basic neuroscience (dissection and staining of brain cells, for example), which each can be quite insightful in cognitive neuroscience.

So, what is the history of these techniques? People have been getting whacks to the head forever, and doctors have been investigating them forever, but a few important patients form the beginning of modern cognitive neuroscience for a few reasons. First, for most of human history, weapons have been high on large blunt force, and low on damage to a specific area. Our ability to gather evidence on what brain area does what (and all of neuroscience is not only what brain _area_ does what, but more on that later) using people who have brain damage is dependent on how big that damage is. Further, the issues of drainage and infection made most head injuries fatal in the short term, if not immediately. I think you could make the case that the first important case in the history of neuroscience was as much to do with gunpowder and the germ theory of disease as anything else.

|

| The comb-over covers his brain! |

1) Dug a deep hole, down to the hard rock

2) Poured some gunpowder in it and set a fuse

3) Filled the hole back up with sand

4) Tamped down the dirt with a long iron rod

5) Light the fuse

6) Run away

This is a dangerous activity. And don't skip step 3. Be very careful that you don't skip step 3, because banging an iron rod directly on gunpowder, with hard rock below, tends to make sparks. Which gunpowder likes. A LOT.

So, poor Phineas skipped step 3, was looking to the side and thought the dirt was in. And the iron pod he was tamping flew up the hole, hit him right under the chin, and flew out the top of his head, taking a big chunk of his brain with it.

But Phineas walked to the hospital, and was "ok" the next day. His personality seemed to change, and he wasn't very good at making decisions, but that was about it.

Let's stop. Do we know what the frontal lobe does? No. And this is just one brain. Just one Phineas. And we don't really know exactly what the damage was, or exactly how much his behavior changed. But it starts to give us pretty good evidence that this part of the brain (or at least that part that got blew out) isn't important for walking or talking or breathing. It establishes some boundaries.

Ok, next stop, Tan. Tan was a patient who could only say Tan. But his doctor noticed that he could also walk, and breathe. Just not talk. Tan did not have a brain injury, but a brain disease. His doctor, Paul Broca, hypothesized that his ability to produce language was disrupted, but his ability to comprehend language was spared. Tan could follow simple directions. When Tan died, Broca did an autopsy and found damage to the brain on a certain part of the left side of his cerebral cortex. Unlike Phineas, Tan was not unique. Broca was a specialist in aphasias, people who had difficulties with language. He had a large set of patients with language problems, and a lot of them who had problems producing language had damage to that area, whether by syphilis (which was Tan's disease) or by gunshot wound.

Another doctor, named Karl Wernicke, had many other patients, who seemed to have no trouble producing speech, but could not understand it. At autopsy, these patients also had damage to the left side of their cerebral cortex, but in a different place than Broca's patients.

Phineas Gage had his accident in 1848, and died 12 years later.

Tan died in 1861.

Wernicke described his group of patients in the 1870's

So, by the time the 1870's are up, we have one famous patient, and several groups of patients, all attesting to a pattern of behavior that correlates to certain kinds of brain damage. This work continues, with people having strokes, getting gunshot wounds in war, and advanced stages of certain diseases. They start to give us a picture of certain brain areas being responsible for certain tasks and behaviors. This has been going on for at least 150 years. What has happened in this time? Similar logic, but we have improved our ability to detect the damage, and describe the behavior. Detecting the damage (in chronological order), with x-rays (1895), PET scans (1961), CT scans (1972), and MRI scans (1977). The scanning technology above only describes anatomical structure (and damage), not brain activity. We'll have to wait for a little until I describe techniques to scan brain activity. Our ability to describe the behavior has also improved, with millisecond timers, or with behavioral technique such as Gazzaniga and Sperry's split brain studies, or the different kinds of standardized neurological exams.

So, what I have described above is one main class of evidence for the connection between brain and behavior. Of course, we are not "there yet" (because there is no "there" there). But at each stage, there is mounting support for a general hypothesis ("Certain areas of the brain serve highly specialized functions") as well as mounting support for individual hypotheses ("The left posterior inferior frontal gyrus is important for processing and producing grammar").

Tomorrow, the second kind of evidence: intentional brain damage or stimulation.

1 comment:

Best. Blog Name. Ever.

More substantive (I hope) comments after the other two sections.

Post a Comment