I spend a lot of time thinking about how to get generally smart and educated people to understand the nature of science. Despite many people's eagerness to dismiss young earth creationists as either deluded or cranks, I think their beliefs are built upon a misconception of science that is remarkably prevalent. When strongly held beliefs meet scientific evidence, the beliefs generally win.

At the end of my history of psychology course, we read Keith Stanovich's excellent "How to Think Straight About Psychology". It is an incredibly readable philosophy of science book, applied to psychology. But even at the end, I have students who I know still doubt evolution, or hold strikingly pseudoscientific or unscientific beliefs. This is not because they are stupid, or haven't studied enough, but because science is quite often counterintuitive, and in most of our school science curriculum, we don't really teach how science works as much as a large set of science facts. Not to diminish the power of facts, because you can't organize anything if there are no facts, but science is not just a series of facts.

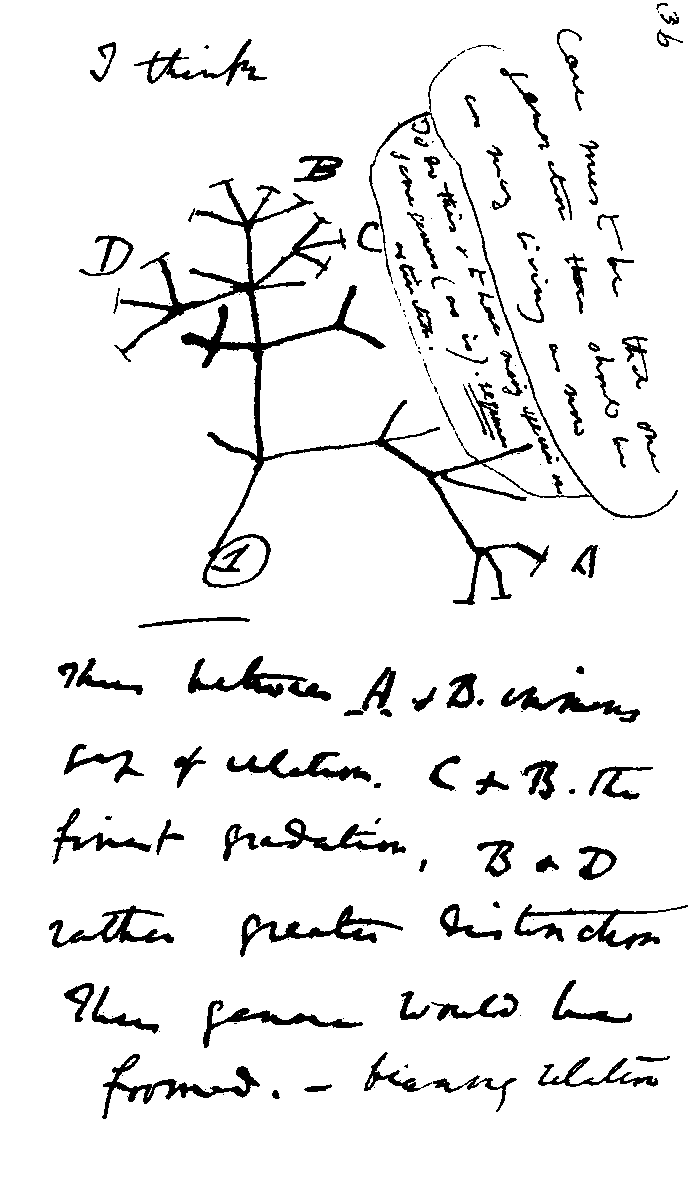

|

| Darwin's first writing of theory of evolution, in 1837, 21 years before Origin was published |

So where does that leave us with evolutionary psychology? Well, evolution explains a great deal of human and animal biology. How does it do with psychology? I am not a big fan of many of the evolutionary and genetic accounts of intelligence, partly because they do not square with my egalitarian beliefs, but also because they may explain some facts, but they do a crappy job of predict any new ones. If the IQ gap between blacks and whites is genetic and fixed, why is there so much evidence that IQ can be changed? Why is there the Flynn effect?

While popular imagination of science hears evolutionary psych and thinks of Kanazawa, or the Bell Curve, the theories of evolutionary psychology are many and diverse. Instead of disparaging the whole field, we should try to be more like scientists ourselves, and tease apart which individual claims of a theory have merit, and which don't. Unfortunately, this often means learning more about the set of facts that the science is trying to organize, or trusting the scientists who know those facts. Too often, instead of learning more, we look down the hole and see darkness, and assume that it is shallow, instead of asking those who have dug, who had reached, who have probed and prodded, to tell us how deep it goes.

No comments:

Post a Comment