Ok, actually, already moved. Over to wordpress.

So, redirect your linker-doodles to:

Http://cedarsdigest.wordpress.com

Friday, July 15, 2011

Tuesday, July 05, 2011

Public Education is a Community Garden

I spend a fair amount of time thinking about where my academic training would help in the education reform debates--in cognitive psychology, in research design and in statistics. But on those rare times when I get to engage someone whose take is largely different from mine, it seems that the evidence is irrelevant. So many in the education debates seem to have entirely different notions of what the American system of public education is. I don't think that people who don't agree with me are evil, greedy, or stupid. But I do think they might be operating under a different metaphorical framing of education than I operate under. So here is a metaphor I have been toying with lately:

Public education is a community garden.

There are many elements that go into the success of a garden. There are different degrees of sun, soil, water, seeds, weeding, and different kinds of gardeners to maintain it.

From far away, our American garden looks both unkempt and unproductive. Wholesalers who weigh our produce at the market look down and shake their heads. Chefs at restaurants say that if we keep at this rate, they won't be able to serve their customers. Then a new crop of architects, after conferring with these chefs and grocery stores, survey our garden woefully, roll up their sleeves and get ready to apply new science and technology and their experience planning buildings to quickly solve the problems of this poorly managed community garden.

The gardeners on the inside have a different view. They see that one side of the garden is thriving. That side has perfect soil and plenty of sun. The seedlings from that side come from an expertly maintained greenhouse. The architects can't see what the gardeners know; this side has a hidden irrigation system that cares for the plants when the gardeners aren't there. The soil is refreshed with compost, lovingly collected and gently spread by the neighbors of that side of the community garden.

The other side of the garden is not so lucky. The soil is hard and barren of nutrition. The trees above give too much shade and pine needles acidify the soil. The seeds must be planted directly, and do not get time in the greenhouse. The hoses are leaky and always breaking.

Gardeners on the inside see and cope with these conditions. The ones on the sunny side come in the morning, and gently trim their plants, shaping them with trellises or tomato cages. They appreciate the superior tools they are given, and how they don't have to hoe every day, or do the grueling tedious work of removing pine needles. The irrigation system lets them wield their spray bottles, polish their fruit, and cultivate a rich and diverse garden of flowers, fruits and vegetables. Yet they appreciate their position, and don't fault the gardeners on the other side for the differences in effects.

The gardeners on the other side have it differently. Some bring a rake from home, and use the handle like a pick ax to loosen up the earth. Others wander around aimlessly picking up pine needles, grumbling that this doesn't feel like the gardening they signed up for. A few dedicated, and often experienced gardeners manage to get flowers to grow out of this awful environment. They have often cleared out the weeds and needles from their area, are doubly proud of their hardy little seeds and their own accomplishments. But most gardeners on this side don't feel that, or only for a season or two. Many realize that they would much rather wield the spray bottle than use the handle of their rake like a hoe and jump into an open spot on the sunny side as soon as they can. Others think they aren't cut out for gardening, and leave the garden altogether, some even become architects. And some give up, lean on their rakes, or sit down and stare off into the distance; ignoring a stray seedling or two, often knowing it won't be enough to take to market.

What do I like about this metaphor?

First, learning as cultivation strikes me as capturing the nature of learning a lot better than the "filling up the head" featured Waiting for Superman, or the "Race" to the Top. It is a more organic process, more obviously complicated.

Second, I think it emphasizes the distortion of the economists such as Eric Hanushek, and policymakers evaluating the entire system as a whole through test scores, comparing to other "community gardens" in other towns (like Singapore, Hong Kong or Finland) just by a crude single metric (perhaps simply weighing the produce?). We have at least two school systems in this country, and the gaps between rich schools and poor schools are stark.

Third, I think it captures the complexity of the situation for the teachers/gardeners. Let me acknowledge a point of the reformers: there are bad teachers. There are teachers who have given up and don't put enough effort into the job. But the next two questions are critical. How many of these are there? In my experience, and that of my friends, siblings and wife, this was small at some of our DC Public Schools. Further, can you be so sure that you can identify the ones who have given up and the ones who are taking a break. I am reminded of John Steinbeck's story about his uncle in his book "A Primer on the 30's" (nice blog post).

It was the fixation of businessmen that the WPA did nothing but lean on shovels. I had an uncle who was particularly irritated at shovel-leaning. When he pooh-poohed my contention that shovel-leaning was necessary, I bet him five dollars, which I didn’t have, that he couldn’t shovel sand for fifteen timed minutes without stopping. He said a man should give a good day’s work and grabbed a shovel. At the end of three minutes his face was red, at six he was staggering and before eight minutes were up his wife stopped him to save him from apoplexy. And he never mentioned shovel-leaning again.”

Many critics of the shovel leaners have no idea what it is like. Others, like Michelle Rhee, leave after three years, after proclaiming success, despite employing questionable methods. And they are right in principle that an amazing dedicated gardener can have a real impact anywhere. A teacher who is willing to work 70-80 hour weeks and shed blood to feed her little seedlings can, with luck and support, coax a flower from the dust bowl. But this is not a way a way to approach a system or grow a profession. Many things matter to student learning. The student's ability, desire and discipline. The school environment, the class size, the resources available, the course content. External factors wreak havoc on any gardener's well planned regimen: Lead paint, family illness, constant relocation.

This metaphor illustrates to me the approach of Diane Ravitch, the SOS March and the skeptics of top-down, market-based reforms They are on the side of the gardeners, defending their hard-worked, but still weedy patch of earth in front of bulldozers. They agree that the current state of the garden is unacceptable, but they don't think bulldozers and a new set of gardeners will help: the soil is still the same, as is the sun, and the water. But before we have a deeper, more sophisticated discussion about different seeds, soil types, what kind of plants we value, we have to stop the bulldozers and stop attacking the gardeners. What would reform look like, you ask? More compost (resources, aides), more water (interesting content), better tools (higher teacher salaries across the board), and maybe a smaller row to hoe (class size). But this is not the same as saying the garden is perfect as it is.

This metaphor also fits with how I view standardized testing. The kind of testing we see seems to be a simple ruler. How high is your plant? Plant height is not a totally irrelevant metric for plant health, but when you push too hard on it (Campbell's Law) it ceases being as informative. What would intense pressure and incentives for taller plants in a community garden cause? The nice sunny side would ignore it at first: My tomatoes are tall and lovely, thanks. On the other side you would see contraptions to stretch every inch. But eventually, people would move away from planting things like pumpkins and squash, or strawberries, and all plant corn. And the narrowing of curricula has started to happen across the country, just as our crop biodiversity has narrowed with the efficient and standardized approach to growing corn and soybeans.

I am sure this metaphorical approach doesn't solve anyone's problems, but for me it is a reminder that it is very hard to agree on how to improve education, if we can't agree on what our education system is.

|

| Photo: Jennifer Cowley (The Constituency for a Sustainable Coast) |

Public education is a community garden.

There are many elements that go into the success of a garden. There are different degrees of sun, soil, water, seeds, weeding, and different kinds of gardeners to maintain it.

From far away, our American garden looks both unkempt and unproductive. Wholesalers who weigh our produce at the market look down and shake their heads. Chefs at restaurants say that if we keep at this rate, they won't be able to serve their customers. Then a new crop of architects, after conferring with these chefs and grocery stores, survey our garden woefully, roll up their sleeves and get ready to apply new science and technology and their experience planning buildings to quickly solve the problems of this poorly managed community garden.

The gardeners on the inside have a different view. They see that one side of the garden is thriving. That side has perfect soil and plenty of sun. The seedlings from that side come from an expertly maintained greenhouse. The architects can't see what the gardeners know; this side has a hidden irrigation system that cares for the plants when the gardeners aren't there. The soil is refreshed with compost, lovingly collected and gently spread by the neighbors of that side of the community garden.

The other side of the garden is not so lucky. The soil is hard and barren of nutrition. The trees above give too much shade and pine needles acidify the soil. The seeds must be planted directly, and do not get time in the greenhouse. The hoses are leaky and always breaking.

Gardeners on the inside see and cope with these conditions. The ones on the sunny side come in the morning, and gently trim their plants, shaping them with trellises or tomato cages. They appreciate the superior tools they are given, and how they don't have to hoe every day, or do the grueling tedious work of removing pine needles. The irrigation system lets them wield their spray bottles, polish their fruit, and cultivate a rich and diverse garden of flowers, fruits and vegetables. Yet they appreciate their position, and don't fault the gardeners on the other side for the differences in effects.

The gardeners on the other side have it differently. Some bring a rake from home, and use the handle like a pick ax to loosen up the earth. Others wander around aimlessly picking up pine needles, grumbling that this doesn't feel like the gardening they signed up for. A few dedicated, and often experienced gardeners manage to get flowers to grow out of this awful environment. They have often cleared out the weeds and needles from their area, are doubly proud of their hardy little seeds and their own accomplishments. But most gardeners on this side don't feel that, or only for a season or two. Many realize that they would much rather wield the spray bottle than use the handle of their rake like a hoe and jump into an open spot on the sunny side as soon as they can. Others think they aren't cut out for gardening, and leave the garden altogether, some even become architects. And some give up, lean on their rakes, or sit down and stare off into the distance; ignoring a stray seedling or two, often knowing it won't be enough to take to market.

What do I like about this metaphor?

First, learning as cultivation strikes me as capturing the nature of learning a lot better than the "filling up the head" featured Waiting for Superman, or the "Race" to the Top. It is a more organic process, more obviously complicated.

Second, I think it emphasizes the distortion of the economists such as Eric Hanushek, and policymakers evaluating the entire system as a whole through test scores, comparing to other "community gardens" in other towns (like Singapore, Hong Kong or Finland) just by a crude single metric (perhaps simply weighing the produce?). We have at least two school systems in this country, and the gaps between rich schools and poor schools are stark.

Third, I think it captures the complexity of the situation for the teachers/gardeners. Let me acknowledge a point of the reformers: there are bad teachers. There are teachers who have given up and don't put enough effort into the job. But the next two questions are critical. How many of these are there? In my experience, and that of my friends, siblings and wife, this was small at some of our DC Public Schools. Further, can you be so sure that you can identify the ones who have given up and the ones who are taking a break. I am reminded of John Steinbeck's story about his uncle in his book "A Primer on the 30's" (nice blog post).

|

| Relief workers in San FranciscoPhoto: Greg Gaar Collection, San Francisco |

Many critics of the shovel leaners have no idea what it is like. Others, like Michelle Rhee, leave after three years, after proclaiming success, despite employing questionable methods. And they are right in principle that an amazing dedicated gardener can have a real impact anywhere. A teacher who is willing to work 70-80 hour weeks and shed blood to feed her little seedlings can, with luck and support, coax a flower from the dust bowl. But this is not a way a way to approach a system or grow a profession. Many things matter to student learning. The student's ability, desire and discipline. The school environment, the class size, the resources available, the course content. External factors wreak havoc on any gardener's well planned regimen: Lead paint, family illness, constant relocation.

This metaphor illustrates to me the approach of Diane Ravitch, the SOS March and the skeptics of top-down, market-based reforms They are on the side of the gardeners, defending their hard-worked, but still weedy patch of earth in front of bulldozers. They agree that the current state of the garden is unacceptable, but they don't think bulldozers and a new set of gardeners will help: the soil is still the same, as is the sun, and the water. But before we have a deeper, more sophisticated discussion about different seeds, soil types, what kind of plants we value, we have to stop the bulldozers and stop attacking the gardeners. What would reform look like, you ask? More compost (resources, aides), more water (interesting content), better tools (higher teacher salaries across the board), and maybe a smaller row to hoe (class size). But this is not the same as saying the garden is perfect as it is.

|

| Corn in a Community Garden, Photo by Ned Raggett |

I am sure this metaphorical approach doesn't solve anyone's problems, but for me it is a reminder that it is very hard to agree on how to improve education, if we can't agree on what our education system is.

Friday, July 01, 2011

David Brooks: C'mon Feel That Invigorating Moral Culture, baby!

David Brooks recent column on education reform is not as immediately awful as many of his other columns. It does not make me want to throw it down in disgust (but in the bestest, smirking-est, Taibbi-est way possible). It does not make me want to mumble die yuppie scum (ok, maybe just a little bit). It has that wonderful brooksian reasonableness, you can just see him with Mark Shields, nodding in resignation in response to something about Sarah Palin while subtly plugging Newt Gingrich’s epic intelligence.

Nevertheless there are some major errors in logic, and a repetition of a troublesome theme of his, which I think merit a line by line criticism.

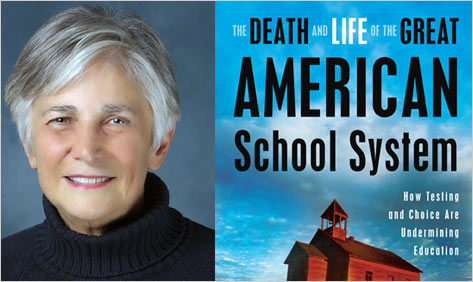

First, he begins with the standard criticism of Diane Ravitch. She is so prolific (“she pours our books”). She gives speeches (sometimes two at the same place! What a blabbermouth!). She is too quick to assign evil motives. Okay, I will acknowledge that I too don’t like her tendency to assail the intentions of some reformers (although “greed-heads?” Really? Is this 2nd grade?).

But you know who else is prolific? Appearing on TV and in the NYT? Writing books? Giving readings? David Brooks. I don’t see anyone debunking Brooks based on the quantity of his output. What hypocrisy for people as prolific as Brooks to resent the attention that Ravitch gets. They should acknowledge two things. First, she cultivates attention by listening to the educators. She is also is an amazingly effective social networker, publicizing teachers' own words along with her own frequent pithy, twitterific turn of phrase. Brooks, being a good writer himself should realize some of Ravitch’s popularity is due to rhetorical skill as well as to audience cultivation. Second, Ravitch touches a nerve. Her power comes not from her awesome institutional power as a Professor at NYU, or from her bully pulpit as a columnist at the New York Times (oops, sorry, that's Brooks), but from the fact that she expresses what so many people are already thinking and feeling, and she is rare in the national media for doing so.

The next paragraph is a straw man (see Paul Thomas' response), but a critical one in the education debate as it highlights what many reformers misunderstand about Ravitch, and misunderstand about resistance to current top-down reform efforts. Brooks identifies these as “the party-line view of the most change-averse elements of the teachers’ unions:”

There is no education crisis:

This is an oversimplification. The argument that Ravitch and many others (if Brooks bothered to read one of her books, he might realize this) isn’t that there is no education crisis, but that this claim rests on two false assumptions. First, there is no single American educational system. Well-off suburban schools have been turning out well-educated future professionals for quite some time now. Second, the current crisis rhetoric ignores the historical data. Ravitch is a historian, and has seen the permanent educational crisis described in every decade of the 20th century. She claims that our present moment is not unique.

Poverty is the real issue, not bad schools.

Again, an oversimplification, but one that Ravitch comes a lot closer to making. But saying “real issue” here obscures Ravitch’s point. While Ravitch may say that addressing poverty with a holistic program (like, hmm, Harlem Children’s Zone, maybe?) is better educational policy than test-based accountability, she is not a nihilist who thinks “bad” schools don’t matter. She is simply saying that poverty is a greater predictor of academic achievement (yes, even test scores) than reformers want to acknowledge, and that trying to identify and punish bad schools is not an effective way to improve them.

We don’t need fundamental reform; we mainly need to give teachers more money and job security.

What does “fundamental” mean here? Ravitch knows that reformers of every age have pledged that the school system needs to be “fundamentally” reformed. Many teachers know this firsthand, suffering from “reform fatigue” as every new turnaround expert boasts of fundamental change. When ed reformers of all stripes use the word “fundamental reform” it means “the way I want to redesign the educational system.” Everyone involved in this debate wants reform. There are many dimensions of reform possible. From class size, to school size, to curriculum, to who is teaching, to how we train them. Take Diane Ravitch, Leonie Haimson, Deborah Meier, E.D. Hirsch or any number of other people involved in education reform for a long time, and you will find many different ideas for reform. Please stop calling your own approach “fundamental” and everyone else’s ideas “change averse” without bothering to understand them. Most of these people have been trying to change the system for most of their careers.

At this point, Brooks steps back from the straw man (Look how reasonable I am! I am not going to attack this straw man I have shoddily erected, I’ll just be passive aggressive and undermine my opponent before I show how reasonable I am and admit that despite her overall craziness, she has some good points). Brooks acknowledges that teaching is a “humane art built upon loving relationships between teachers and students.” A system designed to improve multiple choices test scores distorts that.

At this point, I must acknowledge that that I continue to read Brooks for a reason. His willingness to acknowledge points of the other side does bolster his credibility. “If you make the tests all important, you give schools an incentive to drop the subjects that don’t show up on the exams but that help students become fully rounded individuals. You may end up with schools that emphasize test-taking, not genuine learning” Acknowledging the tension between testing and the humane nature of education buys him back into my good graces.

Oh, wait. I missed that word. “may” As it turns out, this incentive doesn’t have to work the way Brooks says it “may.” Why not? The dehumanizing testing incentive can be overwhelmed by the magic ofthe free market a visionary school leader with a mission. Brooks cites “education blogger” Whitney Tilson (Don’t you mean hedge fund director? Or TFA co-founder? Or finance columnist? or co-author of More Mortgage Meltdown: 6 Ways to Profit in These Bad Times) as delivering the linchpin in his argument here. The schools that are the best indicators of reform, like KIPP and Harlem Success Academy put tremendous emphasis on testing. But they are also the schools most likely to have all those nice things that Ravitch wants: chess, dance, physics, philosophy and Shakespeare. Tests are not the end in these places, but merely a “lever” that their visionary leaders use to get their students interested in school. Here is the message: Accountability schools have tests, but the tests are subverted to a broader mission (and bizarrely, it doesn’t seem to matter whether that mission is character education, Core Knowledge, or performing arts). The charisma of the school leaders and their “invigorating moral culture” (like some sort of super charged educational shower gel) ensure that these schools are not testing centers, but where education comes alive.

Some evidence? No cherry picking here! Oh wait, just kidding. Carolyn Hoxby’s results of studying charters in New York and Chicago. New Orleans (yes, where Arne Duncan said that Katrina was the best thing that happened to the education system there) has doubled the percentage of students performing at basic competency levels and above (yes doubled! Right here in River City! That’s double with a capital “D” that rhymes with “C” that stands for charter school!). What, you are skeptical of doubling academic achievement in a couple of years. Are you a status-quo defender?

First, I can believe that many charter schools in New York and Chicago have good results. But Hoxby’s study does not say why they are better. Imagine the following situation: You are pitting two youth basketball teams head to head. They played several times before, and it has always been very close, but one team recently got new uniforms. The new uniform team crushes the other team. The clothing company crows about the new uniforms being the thing that made the difference. Silly, no? Is this a fair metaphor? Follow me for just a few seconds. To say that the new uniforms made the difference, you would obviously have several good questions. The first one is of course the criticism that Ravitch begins with: selection bias. Did the new uniform team get any new players? Did they cut their lower ability players? This does not have to be a charter skimming only the best students, and need not be nefarious counseling out (although that does happen). It can be the result of a policy that demands a high level of involvement from parents (KIPP and parental involvement link here) ensuring that even across other measures of poverty, motivated parents more able to be involved in their child’s education are able to enroll. This absolutely happens in some charters. This is not a reason to damn the charter school itself, but just to acknowledge that accepting that high attrition cannot be a national model (or even a system- wide model, the students have to go somewhere). New Orleans is a tragic special case of this demographic fact, in that natural decimation does have a way of changing the demographics of a city, including its school system. The second, often neglected point, is that you might ask what other basic differences between the teams. Did one team get more practice? This is an often passed over difference between many charter schools and traditional public schools, that Hoxby acknowledges, charters often have longer school days, and longer school years. Maybe more practice at school helps you be better at school? Just sayin. If you moved beyond the practice question, you might ask about resources. Did the new uniform team get other things besides new uniforms? How do these charter school pay for chess, philosophy, Shakespeare? Oh, maybe it is because of massive fundraising efforts?

The kind of presentation of evidence Brooks engages in here is reminiscent of Matt Yglesias with the magic of bourgeois modes of behavior. They dispense with the first criticism of selection bias (using a lottery study, or a single case study but ignoring other sources of selection bias) and trumpet the new uniforms. This reminds me of many shoddy popular interpretations of psychology experiments. Just because you have dealt with one third variable problem (selection bias) does not mean you get to say that now correlation really does mean causation.

But I don’t hate charter schools. And neither does Ravitch. I would love to see some of the elements of KIPP and Harlem Children’s Zone see more wide acceptance. For one: addressing poverty takes time and money. Rather than trumpet miracle schools that have amazing results with the power of mission, or leaders, or spiritual fervor, acknowledge that money helps when spent wisely, on things that Ravitch wants it spent on, like chess, Shakespeare, philosophy, or the arts, or foreign languages.

Brooks saves his most dishonest, victim-blaming paragraph for near the end, and almost makes me re-read Myers’ epic rant to fortify myself:

I went to DC Public Schools, I worked with a few principals after college in a brief volunteer stint for Hands On DC. My dad has taught at my high school for 15 years, my wife taught at another one for 8 years. The problem is not mediocre people. Please stop handing a charter principal a multi-million dollar budget and a development office and turn around and tell the public school principals to stop being mediocre and work harder on being outstanding with a sense of mission. When charters have as little resources as public schools, they struggle.

At the end of the column, we finally get the Brooks final solution, so much more reasonable than Ravitch: “The real answer is to keep the tests and the accountability but make sure every school has a clear sense of mission, an outstanding principal and an invigorating moral culture that hits you when you walk in the door” You know what, I love my kids' public school. I can volunteer there (to teach chess!) because I am a professional with flexibility in my hours. There is a great principal and a wonderful staff of hard-working teachers. But what makes this school work so well? Dedicated professionals. Active PTA and parent community. A state and district that funds reading aides and math aides (scroll to the bottom), and lower class sizes. An office staff and a full time nurse.

I’ll fight to protect my school with dedicated professionals with resources, a caring community with time and money to give, and a curriculum as full of "interesting science facts" as my son says. And I'll advocate to give the same to as many kids across the country as we can.You can keep your invigorating moral culture, David Brooks.

Nevertheless there are some major errors in logic, and a repetition of a troublesome theme of his, which I think merit a line by line criticism.

|

| Diane Ravitch with a book she recently poured out |

But you know who else is prolific? Appearing on TV and in the NYT? Writing books? Giving readings? David Brooks. I don’t see anyone debunking Brooks based on the quantity of his output. What hypocrisy for people as prolific as Brooks to resent the attention that Ravitch gets. They should acknowledge two things. First, she cultivates attention by listening to the educators. She is also is an amazingly effective social networker, publicizing teachers' own words along with her own frequent pithy, twitterific turn of phrase. Brooks, being a good writer himself should realize some of Ravitch’s popularity is due to rhetorical skill as well as to audience cultivation. Second, Ravitch touches a nerve. Her power comes not from her awesome institutional power as a Professor at NYU, or from her bully pulpit as a columnist at the New York Times (oops, sorry, that's Brooks), but from the fact that she expresses what so many people are already thinking and feeling, and she is rare in the national media for doing so.

The next paragraph is a straw man (see Paul Thomas' response), but a critical one in the education debate as it highlights what many reformers misunderstand about Ravitch, and misunderstand about resistance to current top-down reform efforts. Brooks identifies these as “the party-line view of the most change-averse elements of the teachers’ unions:”

There is no education crisis:

This is an oversimplification. The argument that Ravitch and many others (if Brooks bothered to read one of her books, he might realize this) isn’t that there is no education crisis, but that this claim rests on two false assumptions. First, there is no single American educational system. Well-off suburban schools have been turning out well-educated future professionals for quite some time now. Second, the current crisis rhetoric ignores the historical data. Ravitch is a historian, and has seen the permanent educational crisis described in every decade of the 20th century. She claims that our present moment is not unique.

Poverty is the real issue, not bad schools.

Again, an oversimplification, but one that Ravitch comes a lot closer to making. But saying “real issue” here obscures Ravitch’s point. While Ravitch may say that addressing poverty with a holistic program (like, hmm, Harlem Children’s Zone, maybe?) is better educational policy than test-based accountability, she is not a nihilist who thinks “bad” schools don’t matter. She is simply saying that poverty is a greater predictor of academic achievement (yes, even test scores) than reformers want to acknowledge, and that trying to identify and punish bad schools is not an effective way to improve them.

We don’t need fundamental reform; we mainly need to give teachers more money and job security.

What does “fundamental” mean here? Ravitch knows that reformers of every age have pledged that the school system needs to be “fundamentally” reformed. Many teachers know this firsthand, suffering from “reform fatigue” as every new turnaround expert boasts of fundamental change. When ed reformers of all stripes use the word “fundamental reform” it means “the way I want to redesign the educational system.” Everyone involved in this debate wants reform. There are many dimensions of reform possible. From class size, to school size, to curriculum, to who is teaching, to how we train them. Take Diane Ravitch, Leonie Haimson, Deborah Meier, E.D. Hirsch or any number of other people involved in education reform for a long time, and you will find many different ideas for reform. Please stop calling your own approach “fundamental” and everyone else’s ideas “change averse” without bothering to understand them. Most of these people have been trying to change the system for most of their careers.

At this point, Brooks steps back from the straw man (Look how reasonable I am! I am not going to attack this straw man I have shoddily erected, I’ll just be passive aggressive and undermine my opponent before I show how reasonable I am and admit that despite her overall craziness, she has some good points). Brooks acknowledges that teaching is a “humane art built upon loving relationships between teachers and students.” A system designed to improve multiple choices test scores distorts that.

At this point, I must acknowledge that that I continue to read Brooks for a reason. His willingness to acknowledge points of the other side does bolster his credibility. “If you make the tests all important, you give schools an incentive to drop the subjects that don’t show up on the exams but that help students become fully rounded individuals. You may end up with schools that emphasize test-taking, not genuine learning” Acknowledging the tension between testing and the humane nature of education buys him back into my good graces.

Oh, wait. I missed that word. “may” As it turns out, this incentive doesn’t have to work the way Brooks says it “may.” Why not? The dehumanizing testing incentive can be overwhelmed by the magic of

Some evidence? No cherry picking here! Oh wait, just kidding. Carolyn Hoxby’s results of studying charters in New York and Chicago. New Orleans (yes, where Arne Duncan said that Katrina was the best thing that happened to the education system there) has doubled the percentage of students performing at basic competency levels and above (yes doubled! Right here in River City! That’s double with a capital “D” that rhymes with “C” that stands for charter school!). What, you are skeptical of doubling academic achievement in a couple of years. Are you a status-quo defender?

|

| Taste our invigorating moral culture, vile illiteracy! |

The kind of presentation of evidence Brooks engages in here is reminiscent of Matt Yglesias with the magic of bourgeois modes of behavior. They dispense with the first criticism of selection bias (using a lottery study, or a single case study but ignoring other sources of selection bias) and trumpet the new uniforms. This reminds me of many shoddy popular interpretations of psychology experiments. Just because you have dealt with one third variable problem (selection bias) does not mean you get to say that now correlation really does mean causation.

But I don’t hate charter schools. And neither does Ravitch. I would love to see some of the elements of KIPP and Harlem Children’s Zone see more wide acceptance. For one: addressing poverty takes time and money. Rather than trumpet miracle schools that have amazing results with the power of mission, or leaders, or spiritual fervor, acknowledge that money helps when spent wisely, on things that Ravitch wants it spent on, like chess, Shakespeare, philosophy, or the arts, or foreign languages.

Brooks saves his most dishonest, victim-blaming paragraph for near the end, and almost makes me re-read Myers’ epic rant to fortify myself:

The places where the corrosive testing incentives have had their worst effect are not in the schools associated with the reformers. They are in the schools the reformers haven’t touched. These are the mediocre schools without strong leaders and without vibrant missions. In those places, of course, the teaching-to-the-test ethos prevails. There is no other.The reformers have touched every single public school in our country. NCLB and RTTT have ensured that is the case. By elevating testing in reading and math as THE incentive that matters, accountability-based reformers have demanded change from every single principal, and every single superintendent in the country. But where does this testing have the most impact? In the “failing” urban schools (although don’t worry, we’ll all be failing soon). The highest demands, the most intense pressure is felt by those places that had the most children in special ed, the most children in poverty, the most crumbling school buildings, the least amount of cultural capital, the least potential for PTA fundraising, the least number of functioning bathrooms, the least experienced teachers. But no, that doesn’t matter to Brooks. All they need are strong leaders with vibrant missions. No matter how many times Brooks goes to his thesaurus for “alive” (“alive” “vibrant” what’s one more… oh, how about “invigorating” “passion”) it doesn't hide his privilege, callousness and ignorance.

I went to DC Public Schools, I worked with a few principals after college in a brief volunteer stint for Hands On DC. My dad has taught at my high school for 15 years, my wife taught at another one for 8 years. The problem is not mediocre people. Please stop handing a charter principal a multi-million dollar budget and a development office and turn around and tell the public school principals to stop being mediocre and work harder on being outstanding with a sense of mission. When charters have as little resources as public schools, they struggle.

At the end of the column, we finally get the Brooks final solution, so much more reasonable than Ravitch: “The real answer is to keep the tests and the accountability but make sure every school has a clear sense of mission, an outstanding principal and an invigorating moral culture that hits you when you walk in the door” You know what, I love my kids' public school. I can volunteer there (to teach chess!) because I am a professional with flexibility in my hours. There is a great principal and a wonderful staff of hard-working teachers. But what makes this school work so well? Dedicated professionals. Active PTA and parent community. A state and district that funds reading aides and math aides (scroll to the bottom), and lower class sizes. An office staff and a full time nurse.

I’ll fight to protect my school with dedicated professionals with resources, a caring community with time and money to give, and a curriculum as full of "interesting science facts" as my son says. And I'll advocate to give the same to as many kids across the country as we can.You can keep your invigorating moral culture, David Brooks.

Sunday, June 26, 2011

The web is best when it's arguing

Since I just got back into Twitter I've been thinking more about the strengths and weaknesses of the web. I am going to focus on what I think the internet does right, instead of belaboring what the net is doing to kids brains when they spend all day on Facebook (back in my day, we spent our useless teen time on the phone!). Yes, this is continuing to riff on my Oral Culture vs. Literate Culture post from last week.

I know that looking at Facebook comment wars doesn't back this up, but I think when the internet really shines is arguments. The recent theory by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber about how human reasoning evolved for the purpose of argument uses as evidence findings that people get more reasonable when they argue. In other words, we reason better when we are trying to persuade. I am sure that is not a general rule, but when I read a good point-counterpoint I am struck by how much I can learn -- not just by a journalist saying "he says-she says" but a real back and forth, with supporting evidence from each side, not limited to what will fit in a 1000 word newspaper piece, as interpreted by a generalist.

Ok, exhibit A: Yves Smith shreds Ezra Klein's review of Inside Job. Here's a bio of Yves Smith if you didn't know who she was. Basically what this amounts to is an expert with 25 years of experience taking down a hasty journalistic essay, piece by piece. Yes, it has some scholarly ass-kicking, reminiscent of the letters section of the NYRB, but it backs it up with links and evidence. Smith is relentlessly critical of Klein, but retains an appreciation for the storytelling ability of Michael Lewis, Klein's apparent "expert" in explaining the financial crisis. The piece is very long, but I found it very illuminating, and synthesized a lot of my conclusions about the financial crisis: We should not blame a few evil greedy bankers at the top, nor should we shake our heads and say that our international banking system is so complicated no one could have predicted it. This was a systemic diffusion of responsibility, much like the bystander effect, a well-documented phenomena in social psychology in which people are less likely to aid someone in need when there are many bystanders. Further, it was a complete capture of the levers of regulation by the industry meant to be regulated. By the way, some comments are typical bickering, but there was one that included a long review of Inside Job, by Dave Stratman, who seemed to be basing it on his earlier review.

Why did I like this? Because it was not just someone explaining the financial crisis, but arguing with other people, explaining why they were wrong (or incomplete). Why does it show what's great about the web? Because I think the role of the generalist journalist is (and should be) declining. Previously, popular modes of mass communication were limited by space (newspaper columns) and time (deadlines, no journalist can be expert in everything they cover) in a way that they are not now. I don't need the New York Times to employ a sociologist of technology, but when an issue comes up, I would rather read Zeynep Tefukci than Bill Keller when considering the effects of twitter. She is a professional in that field, knows a lot of the evidence, thinks about this stuff when she goes to bed at night, and has several days to follow many of the different subthreads of Keller's argument. Keller, a really really smart guy, can read the articles that Tefukci sends, criticize them and then cites as evidence in response the following:

I know that looking at Facebook comment wars doesn't back this up, but I think when the internet really shines is arguments. The recent theory by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber about how human reasoning evolved for the purpose of argument uses as evidence findings that people get more reasonable when they argue. In other words, we reason better when we are trying to persuade. I am sure that is not a general rule, but when I read a good point-counterpoint I am struck by how much I can learn -- not just by a journalist saying "he says-she says" but a real back and forth, with supporting evidence from each side, not limited to what will fit in a 1000 word newspaper piece, as interpreted by a generalist.

|

| Yves Smith |

|

| Zeynep Tefukci |

My sense of Facebook, not based on research but based on some experience and observation, is that for some people Facebook creates a kind of friendship that is more superficial than the kind that grows out of hours spent together in one another’s company. Of course, social media is a way to keep in touch with real friends and expand your network of more casual, less intimate relationships. But it also makes it possible to feel like you have a meaningful social life when, in reality, you are missing something. I did not offer this as a scientific fact but as an observation and a concern.He ends the letter with a smarmy, "and now I have to go earn a paycheck." This is exactly it. If I am interested in this issue, I want somebody like Tefukci, who looks for evidence, interprets it within a context of other evidence, who is dogged and persistent. If some evidence is lacking, then look for more. (Here is more, by the way). I want to read someone who wants to stick around and argue, I don't want someone to make a few "observations," share a few "concerns," and then leave. I don't want a smarter generalist, who's got great "general critical thinking skills" and is an expert at making anything readable, a nice narrative, and interesting. I want someone who has found this issue interesting for 25 years, and is going to find this issue interesting for another 25. I'll skim a little, forgive typos, ignore a little jargon here and there, follow and appreciate the links. And I'll tune in more and more, to my trusted sources on specific issues, not a single trusted source on general issues.

Thursday, June 23, 2011

Practical Wisdom and College Teaching

|

| Twas love at first sight! (At the 6th grade science fair) |

|  |

| At the beginning of every semester ... | and at the end. |

Don't mistake this for an overall judgment of my failure as a teacher. The students felt like they learned something, and they did actually learn something from my past classes. But I have always been painfully aware of the huge missed potential for learning and inspiration. The gap between those two quantities have always gnawed away at my soul as I read over the final exams, or question the students in future classes. Any teacher who thinks the students learn their content perfectly should have the (always humbling) experience of having that student in a class a year later. But I learn from these failures, and I love being in a field where I can learn from failures without fear (i.e. practice).

|

| It is impossible not to be wowed by the Lilac Chaser |

But most of what I have learned cannot be translated into words. This is embedded in the very nature of the practice of any craft, and in the nature of the practical wisdom that Aristotle described : it is context-specific and escapes general, rule-based summary. There is no one right pedagogy, there is no one right way to teach General Psych, or one right way to teach kindergarten. There are a few principles, that are right, most of the time, in most situations, which are good at guiding better practice. What I have learned is likely a lot more specific than even I realize. It may be specific to my teaching persona, or to that particular class, or to my subject, or to the age of my students. I am always surprised at how different 18-year-olds are from 22-year-olds, and this means that teaching each cannot simply conform to a few general principles.

|

| Next post: A history of Psychology in beards |

|

| It's not turtles, it's practice, all the way down |

More pressure to precisely measure the learning narrows teaching, and narrows learning. The successful assessments that I have seen are formative, not evaluative. No matter the evaluation, the instant that pay, or hiring and firing gets tied to them, they become hammers instead of scalpels. We may be able to boost that particular metric if we push really hard, but that often comes at a cost of other outcomes that may be harder to measure but are not necessarily less valued. Sometimes, that outcome is acceptable. In Atul Gawande's The Checklist, he describes how pilot checklists have ensured the remarkable safety record of the commercial airliner. But I suspect this emphasis on safety has come at a cost to innovation, energy efficiency, and price (whatever happened to Valujet?). We may be ok with an overwhelming priority on safety for airplanes, but in higher education, narrow accountability will crowd out many other worthy goals, not to mention people who value academic freedom and the ability to cultivate their practical wisdom.

Ultimately, part of the reason I love what I do because I can feel myself getting better at it (the teaching and the scholarship, if not the pithy blog posts) and I can enjoy the fruits of my labor. These fruits are not merit based pay, but the tiny lights of inspiration, of comprehension, of curiosity, going off in the deep recesses of my students' minds. The sparkly warm glow of reading about a new finding in embodied perception. A profession is defined by practical wisdom, and practical wisdom is not dispensed like manna from the talented, but generated by accident by people just trying to get better at something they find interesting.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Book Review: Practical Wisdom

Practical Wisdom

By Barry Schwartz and Kenneth Sharpe

The premise of this book, written by a psychologist (Barry Schwartz, also author of Paradox of Choice) and a political scientist (Kenneth Sharpe), is that we have a society with too many rules and perverse incentives that discourage the cultivation and use of practical wisdom. This may sound at first glance like a modern rehashing of a libertarian perspective, that we should let individual freedom and market forces lead us all to greater happiness and stop meddling government rules and bureaucrats.

But this book deftly shows how de-humanizing incentives can corrupt and undermine practical wisdom in many large institutions, whether they be a public school or a private hospital. The book is split into four sections. First, what is practical wisdom and why do we need it? Second, the machinery of wisdom. Third, the war on wisdom, and finally, sources of hope.

What is practical wisdom? It begins, say the authors, with Aristotle, who described what he called phronesis. Aristotle’s wisdom in Nichomean Ethics was not a theoretical system of moral rules, but a specific, practical ethics, impossible to describe in general terms. Doing the right thing was not a matter of just knowing the right rules, but knowing the right thing to do, in the right circumstances, with the right person at the right time. And this takes practice. This moral dimension of practice is a compelling one for me, and resonates with how I approach becoming a better teacher.

In the machinery of wisdom, they cover several bits of familiar (for me) territory in modern research in psychological science. First, that decision-making is critically dependent on our emotions. Without emotions, there are no decisions, and without empathy, there is no wisdom. Second, science has a desire to find hidden patterns, the unseen rules that drive our clockwork universe. Science has been wuite successful in this effort, but our human worlds, of education, of law, of medicine, are not at all clockwork, and so complex and uncertain, that rule-based approaches are doomed to fail. Examples of this abound in artificial intelligence research, where we have thought that giving robots cameras, microphones, and an amazing analytical processor would quickly give us computers that could do simple human tasks, like navigate our environment, understand language and recognize objects and faces. But even these simple tasks have proven to be monstrously difficult, because we are doing what our brain does best in these cases, which is to cope with uncertainty and make good educated guesses. Most computers, while amazing when given a good set of rules in a rigid, predictable environment, are terrible in situations that are context-dependent or uncertain.

In the machinery of wisdom, they cover several bits of familiar (for me) territory in modern research in psychological science. First, that decision-making is critically dependent on our emotions. Without emotions, there are no decisions, and without empathy, there is no wisdom. Second, science has a desire to find hidden patterns, the unseen rules that drive our clockwork universe. Science has been wuite successful in this effort, but our human worlds, of education, of law, of medicine, are not at all clockwork, and so complex and uncertain, that rule-based approaches are doomed to fail. Examples of this abound in artificial intelligence research, where we have thought that giving robots cameras, microphones, and an amazing analytical processor would quickly give us computers that could do simple human tasks, like navigate our environment, understand language and recognize objects and faces. But even these simple tasks have proven to be monstrously difficult, because we are doing what our brain does best in these cases, which is to cope with uncertainty and make good educated guesses. Most computers, while amazing when given a good set of rules in a rigid, predictable environment, are terrible in situations that are context-dependent or uncertain.So what is the war on wisdom? The authors begin with judges and mandatory minimums. Mandatory sentencing guidelines erode judges’ ability to make individual decisions based on the circumstances. In other words, it takes away their power to judge. Doctors, through financial incentives are nudged into doing more procedures and seeing more patients per day. Teachers are given strict guidelines on what to teach on what days. Or if they are not, are nudged towards teaching to a specific high stakes test.

Why do we have this war on wisdom? Of course no one is anti-wisdom, but well-intentioned efforts designed to encourage other characteristics have had horrible side-effects on practical wisdom. In medicine, a value of higher patient autonomy has led doctors to present options, but refuse to give their own (expert) opinions. In law, the system where lawyers are strictly advocates for their clients, rather than also representatives of the court has led to a disregard for the truth and wise solutions. Further, the desire to fully account for their time, and the competitive nature of making partner, has shaped the legal profession for the worse. The “science” of accountability in the legal profession has eroded the wisdom of the profession. In teaching, seeking to consistently train new teachers and set minimum standards has led to undermining teachers’ ability to learn through practicing their craft.

What are the sources of hope? In law, the authors praise special veterans courts, where judges design sentences and programs to balance the goals of rehabilitation and safety. In legal training they cite a clinical approach to teaching law, preparing law students using a mentoring apprenticeship. Like many in education, they propose a portfolio system for evaluating students and teachers, with flexible criteria, allowing teachers to work within their curriculum, with their own judgment.

While the prose and argument was sometimes a bit lengthy (he says in his typically long-winded blog post), I really recommend this book. It integrated disparate thoughts I have had on large political questions that don’t seem to be engaged by any politicians, or any political party. I can see how simply leaving people entirely alone to practice (whether it be teaching, judging or healing) could be corrupting, but the dehumanizing system we currently have is corrupting in a different way, and we seem to be heading further down that road.

In the next post, I am going to pivot on this, and try to integrate some of the insights from this book with another of my intellectual touchstones, Atul Gawande’s The Checklist, and apply them to my own teaching practices.

Other resources:

- The authors have a Psychology Today blog, whose theme is practical wisdom

- Wired interview with Schwartz about the book

- Barry Schwartz gives a TED talk on Practical Wisdom (23 minutes)

One more supporting link (maybe more to come)

- From Vaughan Bell at MindHacks: Medical school reduces empathy

Thursday, June 16, 2011

Reasonable Doubts about "The Brain on Trial"

I agree with a lot of what David Eagleman has to say in "The Brain on Trial" in this month's Atlantic, and I find him an interesting and provocative thinker. But I had a few reservations.

I agree with a lot of what David Eagleman has to say in "The Brain on Trial" in this month's Atlantic, and I find him an interesting and provocative thinker. But I had a few reservations.First, let me say that I have been reading a lot about him lately, and I read his book about how the internet can save civilization (on the iPad), and it was interesting.

Some of these ideas have been stewing since he gave a talk on the topic of neuro-law here at Randolph-Macon College a few months ago. I had the unique pleasure of getting to talk to him for about 45 minutes in my office. I was a bit star struck at the time, but would have been even more so had I known he was about to be profiled in the New Yorker (by Burkhard Bilger, no less!).

Ok, a quick overview for those of you who don't want to follow any of the links above:

He argues that we should redesign our legal system to reflect how much we know about the brain.

What relevant findings does modern neuroscience tell us? First, the amount of free will we have is on a spectrum. No argument there, we don't hold children as blameworthy as adults, and we make allowances for accidental deaths, or the insanity defense. But second (and this is important) we don't have as much free will as we think we do. A lot of modern psychology and neuroscience show how our unified sense of our conscious thoughts controlling our actions is an illusion. Not only that, but in certain situations we we can look at the brain, and tell how much free will someone has (tumor in the frontal lobe, you lose control of yourself). And we can look at a loss of free will, and predict what we are going to see in the brain (you are losing control of yourself, maybe something is wrong with your frontal lobe).

How should this be applied to the legal system? Eagleman urges to drop assessment of blameworthiness, or intent altogether, and instead look to the future, at reducing recidivism. If we can tell whether someone is likely to commit another crime, that should influence how our legal system deals with them. He argues that we have a lot of good actuarial data on predicting recidivism, and that as neuroscience matures further, we will get even better predictions about who will commit another crime. If we care about the safety of our populace, and the reform of our criminals, why don't we position the legal system to prevent crimes, instead of simply reacting to them?

What's not to like? I agree that our legal system could be better, and more fair, if we took into account recidivism rates, and incorporated crime prevention programs like drug treatment instead of simply punishing and imprisoning. And I agree that we should recognize that dealing with lead paint is a great crime prevention program. But here's where I am skeptical of Eagleman's neuro-optimism:

We don't need neuroscience for any of this.

We can (and should) make our legal system forward-looking because we should recognize that a legal system should not just punish wrong-doing but reduce the circumstances that lead to crime. Exposure to lead paint, drug addiction, and PTSD are all things to be treated, not to be punished.

Social programs and policies should be designed with the knowledge that we have less free will than we think we do. Watson and Skinner said this 75 years ago. Yes, they overreached, and Chomsky and the computer revolution led us away from rats, pigeons and the brain as a black box and towards the mind as an information processor. Another way of putting this is: the environment is powerful. Eagleman believes his knowledge of brain areas and circuits puts him in a different league than Skinner and the behaviorists, but his argument is not that different. And he is not really any closer to scanning someone's brain and predicting a complex behavior.

As Michael Gazzaniga, an esteemed neuroscientist, mentioned off-hand at his talk at the Association for Psychological Science this year: There are frontal lobe patients who lose control and kill people, but many more who don't. And plenty of serial killers don't have frontal lobe abnormalities. Basically, while we can make a probabilistic judgment that damage to the frontal lobe is more likely to impair your judgment than damage anywhere else, we can't make an individual judgment that one person's actions are due to a particular element of their brain anatomy or chemistry.

Finally, there is one piece of the article that for me represents a lot of what bugs me about his approach (and it is not uncommon in modern neuroscience). He describes a prefrontal workout, "in which the frontal lobes practice squelching the short-term brain circuits." In what amounts to a super charged, fMRI -sophisticated biofeedback system, you see the pattern of brain activity that corresponds with craving, and then you try to reduce that pattern of brain activity. This just seems odd and incredibly indirect to me. We don't want to reduce brain patterns. We want to reduce cravings. There are some decent ways of reducing cravings, at least for cigarettes. Eagleman ignores effective psychological treatments and therapies, while trumpeting the dubious triumphs of Prozac, thinking that at some point we will understand the brain enough to directly hack its circuitry. We certainly know a lot more about how the biology of the brain relates to behavior than we did 20 or 30 years ago.

But sometimes the best way to change behavior, is to change behavior, and measure behavior.

In the end, I am a big fan of David Eagleman. His energetic mind, his boundless joy and love of science and his optimism are a wonder to behold. For someone with such confidence in his ideas of applying science to solve the problems of society, he was disarmingly modest and patient with all the questions I saw him answer during his short stay in Ashland. I hope he succeeds in his aim of making our legal system more forward thinking, environmental, and less black and white when it comes to free will. But I wish the wide-eyed optimism about what neuroscience can do was tempered with some acknowledgement that neuroscience isn't the last word on the human condition.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

How the internet make us smart, but makes us feel like idiots

My last post was about a science blog-world kerfuffle. Since I had spent hours looking over these comments, on a few different blogs, trying to pull together the story, and another hour or two writing my post, applying my expert knowledge on how important content knowledge is, I thought I might offer to write a guest blog at the Sci Am blogs about it, and what is to be learned from it all.

The gracious editor responded promptly and gently let me down. Of course, I was two weeks late, and had only grazed the surface of this debate, which played out over more blogs than I realized, as well as on twitter. So I was struck by the irony. Here was a conversation that I felt made me smarter, as I could see the thought processes on display as scientists, journalists and and a collection of otherwise very smart people publicly turned over these ideas in their heads. But in retrospect I realize now that I was only seeing half the conversation, and not even fully comprehending the context and background of that half that I did see. In other words, even as I felt like I was probing deeply, I was made painfully aware that I was scratching the surface.

Which is an odd paradox of the internet. On the one hand, you can learn just about anything you want with a few felicitous keystrokes. On the other, as you do, you realize how ignorant you really are. Kind of similar to grad school that way. Just as you think you know a lot about a topic, you find someone who has spent years exploring a small slice of that topic.

The thing for me is that this is the _best_ way to use the internet. Otherwise, we run the risk of creating our own information bubble, nodding our heads at people who agree with us but don't challenge us, and failing to confront the boundlessness of our ignorance. The price we pay for valuing education is that we must also seek out ignorance and misunderstanding.

But confronting our own ignorance is uncomfortable and feels shameful. Well. At least for me it did. But I tell myself that the sting is necessary to prod us to learn more... and eventually, confront more ignorance and start the whole damn cycle again.

The gracious editor responded promptly and gently let me down. Of course, I was two weeks late, and had only grazed the surface of this debate, which played out over more blogs than I realized, as well as on twitter. So I was struck by the irony. Here was a conversation that I felt made me smarter, as I could see the thought processes on display as scientists, journalists and and a collection of otherwise very smart people publicly turned over these ideas in their heads. But in retrospect I realize now that I was only seeing half the conversation, and not even fully comprehending the context and background of that half that I did see. In other words, even as I felt like I was probing deeply, I was made painfully aware that I was scratching the surface.

Which is an odd paradox of the internet. On the one hand, you can learn just about anything you want with a few felicitous keystrokes. On the other, as you do, you realize how ignorant you really are. Kind of similar to grad school that way. Just as you think you know a lot about a topic, you find someone who has spent years exploring a small slice of that topic.

The thing for me is that this is the _best_ way to use the internet. Otherwise, we run the risk of creating our own information bubble, nodding our heads at people who agree with us but don't challenge us, and failing to confront the boundlessness of our ignorance. The price we pay for valuing education is that we must also seek out ignorance and misunderstanding.

But confronting our own ignorance is uncomfortable and feels shameful. Well. At least for me it did. But I tell myself that the sting is necessary to prod us to learn more... and eventually, confront more ignorance and start the whole damn cycle again.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Getting smart about Wise Crowds, or Some stuff even really smart people don't know about science

I found a discussion between scientists, science writers, and journalists online that I found really fascinating, I thought I would share thoughts here. It relates to a few common themes of mine: that scientific thinking is unnatural, and that statistical thinking is unnatural, the role of content knowledge in critical thinking, and that we should have some role for expertise in interpreting scientific results.

The discussion began with a column by neuroscience writer Jonah Lehrer, about a phenomenon called "the wisdom of crowds." Basically, the idea is that when estimating something very uncertain, sometimes the average crowd response can be "wiser" or more accurate, than even most expert responses. The classic example is from Francis Galton, who observed that the average crowd response for estimating the weight of a steer was better than most of the butchers who guessed. Lehrer's column was about a paper which showed that this wisdom of crowds phenomenon can be reduced (i.e. crowds get less wise) by making the crowd interact with each other.

Ok, so we're fine so far. The brouhaha begins when Peter Freed, M.D., an actual neuroscientist, writes a ranty blog post entitled "Jonah Lehrer is Not a Neuroscientist." He calls Lehrer to task for using "for example" when cherry picking a certain description of data from the paper. In other words, Lehrer acted as if the number he was citing was representative, when it was not. Freed uses this as a way of highlighting the difference between scientists, who look at data all day, and science writers, who do not. But Freed himself makes an error (and he confesses, and makes it part of his blog post) in confusing the median and the mean as measures of central tendency in this case.

Ok, now, maybe I have lost some of you, and I am going to back up just a second, because this is where I think it gets interesting. It depends on a (relatively) nuanced understanding of the three words I used above: median, mean and central tendency.

The vast majority of science that I am aware of takes a set of observations, and looks to describe those observations using some sort of quantitative measure. We don't want to compare apples and oranges, but once we are measuring all apples, we have a set of numbers, and we summarize those numbers to describe the group as a whole. Most of us are familiar with the word "average," and we don't give it any thought. It seems as if an average (adding up all of the numbers and dividing by the number of observations) is a natural, real, description of the set of apples we have in front of us.

But there are different kinds of ways to describe a group of numbers. We can say the most frequent response (called the mode, as in, "9 out of 10 dentists ranked it first"), or the middle response (called the median, when you take the SAT three times, and get a 2000, 2100, and a 1000, you want to count the median response, 2000, not the mean, which would be 1700). The most common is the mean, which most of us consider synonymous with average., as in, "When Bill Gates is in the room, everyone in that room is, on average, a millionaire." This is not even getting into the difference between the geometric mean and the arithmetic mean.

So first, a key point here is that none of these descriptions are more "true" or accurate descriptions of a set of data, they are simply one of many descriptions. This is a mistake made by Nicholas Carr in his blog post discussing Lehrer's column, as he argues that

Carr draws the line between the real-world itself (which he identifies with the arithmetic mean) and a statistical fiction. None other than Kevin Kelly (among others) takes issue with Carr on this point in the comments, which I think are really worth a read.

Given that we accept that all descriptions of a set of data are to some degree interpretation, not simply observation, where do we go from here? In a follow up post, Freed describes the lambasting he received from some of his critics, and relates a funny (fictional) story about his third grade class as it relates to the choice between median and mean. The critical moment is when the principal writes to the statistical research firm: "You may know a lot about statistics, but you don’t know anything about third graders. You get an F, for Fired"

Which leads me to my main point. Statistics is not a purely "scientific" position or a purely aesthetic decision, as Freed claims in a comment on another blog post, by the physicist Chad Orzell. The statistics that scientists use reflects both a basic understanding of distributions of data (what it means when there are a lot of extreme responses, leading to skew, or other non-normal conditions). But the statistics used also depend critically on some knowledge of the phenomena itself. When cognitive psychologists analyze reaction time data, they not only look at the distribution of responses (which will just about always be right skewed) but also consider the task that they are reacting to. What does it mean when most people take 1 second to respond, but a few take 2 minutes? Is that "real" data, or did they fall asleep, or answer their cell phone?

As Orzel points out, there are valid criticisms that one can make about use of statistics in pop science, but at some point, you have to engage with the actual science of the article. In this case, there is a rich literature of making a decision under uncertainty, and the phenomenon of the wisdom of crowds. To criticize the pop science writing, you need to know something about that science, which Freed seems not to. Not only that, Freed celebrates it:

Where are the lessons in all of this?

Lesson #1: Even really smart people make mistakes about science. Even scientists make mistakes about science, especially when not directly in their area of expertise. We should be wary of treading into another field of science, proclaiming it "over" and declaring that our domain is "radically more complex." The scientists working in that field are smart people who have found it to be plenty complex.

Lesson #2: When smart authors and their critics engage in a well-moderated comment section, it can be an amazing way to learn. The commenters on the posts above are generally articulate and educated about the topics. Lehrer responds to Freed in his comment section. Nicholas Carr's post in particular features an honest and thoughtful exploration and arguing with people. To me, this supports the recent theory that people are more reasonable when they argue because human reason exists not to discover truth, but to persuade other people.

Lesson #3: You can learn a lot by reading a few good posts and comment sections, but there is still great value in subject matter expertise. In this case, as Orzel entreats us, actually read the article by the scientists who did the study in the first place. But we should also recognize that many of the sentences in that article are the result of thousands of thousands of hours of work by many experts in this field.

Oh, and also, Jonah Lehrer pretty much had it right in the first place. Which he does most of the time, in the limited amount of space he has for a newspaper column. I remain a fan.

A little postscript: Someone pointed out that I was too hard on Freed, who was gracious in engaging his commenters, and offered a good model for how a scientist reads a paper. He also pointed out that Lehrer brought up the wisdom of crowds paper as a way to join the whole "internet is making us stupid" crowd, which I agree is not true. I am not an Eagleman/Kelly/Shirky, "the internet is going to save civilization" optimist either. But I find many of the traditional journalists decrying the internet (twitter, blogs etc) mostly unconvincing. He also pointed out that this was old news (like two weeks ago!) and that there was a lot to it that I missed. So, now I am on twitter. We'll see how that goes.

The discussion began with a column by neuroscience writer Jonah Lehrer, about a phenomenon called "the wisdom of crowds." Basically, the idea is that when estimating something very uncertain, sometimes the average crowd response can be "wiser" or more accurate, than even most expert responses. The classic example is from Francis Galton, who observed that the average crowd response for estimating the weight of a steer was better than most of the butchers who guessed. Lehrer's column was about a paper which showed that this wisdom of crowds phenomenon can be reduced (i.e. crowds get less wise) by making the crowd interact with each other.

Ok, so we're fine so far. The brouhaha begins when Peter Freed, M.D., an actual neuroscientist, writes a ranty blog post entitled "Jonah Lehrer is Not a Neuroscientist." He calls Lehrer to task for using "for example" when cherry picking a certain description of data from the paper. In other words, Lehrer acted as if the number he was citing was representative, when it was not. Freed uses this as a way of highlighting the difference between scientists, who look at data all day, and science writers, who do not. But Freed himself makes an error (and he confesses, and makes it part of his blog post) in confusing the median and the mean as measures of central tendency in this case.

Ok, now, maybe I have lost some of you, and I am going to back up just a second, because this is where I think it gets interesting. It depends on a (relatively) nuanced understanding of the three words I used above: median, mean and central tendency.

The vast majority of science that I am aware of takes a set of observations, and looks to describe those observations using some sort of quantitative measure. We don't want to compare apples and oranges, but once we are measuring all apples, we have a set of numbers, and we summarize those numbers to describe the group as a whole. Most of us are familiar with the word "average," and we don't give it any thought. It seems as if an average (adding up all of the numbers and dividing by the number of observations) is a natural, real, description of the set of apples we have in front of us.

But there are different kinds of ways to describe a group of numbers. We can say the most frequent response (called the mode, as in, "9 out of 10 dentists ranked it first"), or the middle response (called the median, when you take the SAT three times, and get a 2000, 2100, and a 1000, you want to count the median response, 2000, not the mean, which would be 1700). The most common is the mean, which most of us consider synonymous with average., as in, "When Bill Gates is in the room, everyone in that room is, on average, a millionaire." This is not even getting into the difference between the geometric mean and the arithmetic mean.

So first, a key point here is that none of these descriptions are more "true" or accurate descriptions of a set of data, they are simply one of many descriptions. This is a mistake made by Nicholas Carr in his blog post discussing Lehrer's column, as he argues that

As soon as you start massaging the answers of a crowd in a way that gives more weight to some answers and less weight to other answers, you're no longer dealing with a true crowd, a real writhing mass of humanity. You're dealing with a statistical fiction. You're dealing, in other words, not with the wisdom of crowds, but with the wisdom of statisticians. There's absolutely nothing wrong with that - from a purely statistical perspective, it's the right thing to do - but you shouldn't then pretend that you're documenting a real-world phenomenon.

Carr draws the line between the real-world itself (which he identifies with the arithmetic mean) and a statistical fiction. None other than Kevin Kelly (among others) takes issue with Carr on this point in the comments, which I think are really worth a read.

Given that we accept that all descriptions of a set of data are to some degree interpretation, not simply observation, where do we go from here? In a follow up post, Freed describes the lambasting he received from some of his critics, and relates a funny (fictional) story about his third grade class as it relates to the choice between median and mean. The critical moment is when the principal writes to the statistical research firm: "You may know a lot about statistics, but you don’t know anything about third graders. You get an F, for Fired"